Domestic interventions [alison owen]

Housework, 309 Edgecombe Avenue

Tracey Goodman and I have been friends for more than a dozen years. We met in the Bronx Museum’s Artists-in-the-Marketplace program, we’ve been in shows together, and once we shared a studio space. Our lives are woven together in many other more quotidian ways besides. Being in her apartment studying and making responses to the space (always on days when she was at work) felt like a strange yet logical extension of our friendship.

Her home seems to be a thing that has grown up around her organically. There is a decorative logic that is the result of years of following a specific art practice and aesthetic path. Her colors are subtly different from the ones I’d choose: I’m also a big fan of pink and blue, for example, but she favors cool shades while I favor warm. Everything: from the clothes she wears, to the art she makes, to the space she lives in, feels like an extension of her personality. It’s an expansive and generous mix that includes her grandma’s knickknacks, vintage 1980s dresses, books of feminist theory and poetry, her friends’ artwork, her overweight cat Tulip, and some pretty amazing mid century furniture (mostly found on the cheap and revamped).

I tracked and recorded. I traced the way light moved across her wall over the course of the day, using masking tape and thread as a marker. I brought out my coloraid paper and created palettes that matched the things I especially loved. I made little paintings of the patterns of some dresses and textiles, like a handmade swatch book. Her bathroom had a strangely tiled floor: over the years new and different tiles were inlaid to replace broken ones. Into this floor I pressed clay, creating slabs that I then used to make vessels and plaques.

And the books. One thing I love about borrowing books from Tracey is that she is a prolific underliner and marginalia-maker. Before I started the installation, in response to her fascination with indigo (which has made its way into several of her projects), I had recommended the book Bluets by Maggie Nelson. I found a copy in her house, all marked up. I read it through again (it’s a book I read often, I’d recommend it to you, too, most likely). I compared the way that we read the book. How could you miss that phrase?! I’d think when I read a favorite part that she hadn’t underlined. Or I’d read her margin note and suddenly see something I hadn’t noticed before, see it from her point of view. I created a hand-typed, bound copy for her of just her underlined parts, floating around on the page in relation to where they were in the original text.

We planned a joint opening/housewarming party. A bunch of friends came over. We talked about how her the little apartment was, how happy we were to be in it like this, all together. Everyone got to wander around studying things up close, under the guise of checking out the installation.

Tracey said she lived with my readjustments for a long time, but eventually she had to move all the books back to the bookshelf, from where I’d clustered them on a credenza to frame/echo a painting that was hung above it. She needed her books for reference and for lending, and my system was too different from hers. Fair enough.

The following is written by Skye Gilkerson, in response to Alison’s installation in her home (@skyegilkerson, skyegilkerson.com)

Alison Owen Is In Love With You

Attention is the rarest and purest form of generosity.

-Simone Weil

Alison Owen's site responsive installations highlight the otherwise overlooked elements of the gallery and domestic spaces where she exhibits.

Through a process of research that involves observing the environment over a matter of days or weeks, Owen notes the social, architectural, and natural elements that comprise the heart of a space. From this initial survey she creates compositions throughout the rooms with a variety of found materials, such as using string and tape to trace shadows across the wall, or pressing clay into existing tiles to use as surface pattern for new forms.

According to Owen, her intention is to “draw viewers into a more interactive relationship with architecture,” inviting them to reconsider the history of the spaces they encounter.

***

My own recent experience of Owen’s work unfolded over time through numerous layers of surprise. While I was away at a 10 day silent meditation course, I gave her keys to the home I share with two housemates, so that she could prepare for her exhibition in the common space where we host art shows.

During the sometimes intense and often bizarre world of silent meditation where days feel like centuries, it was comforting to remember that all the while my home was being quietly examined, tended and transformed.

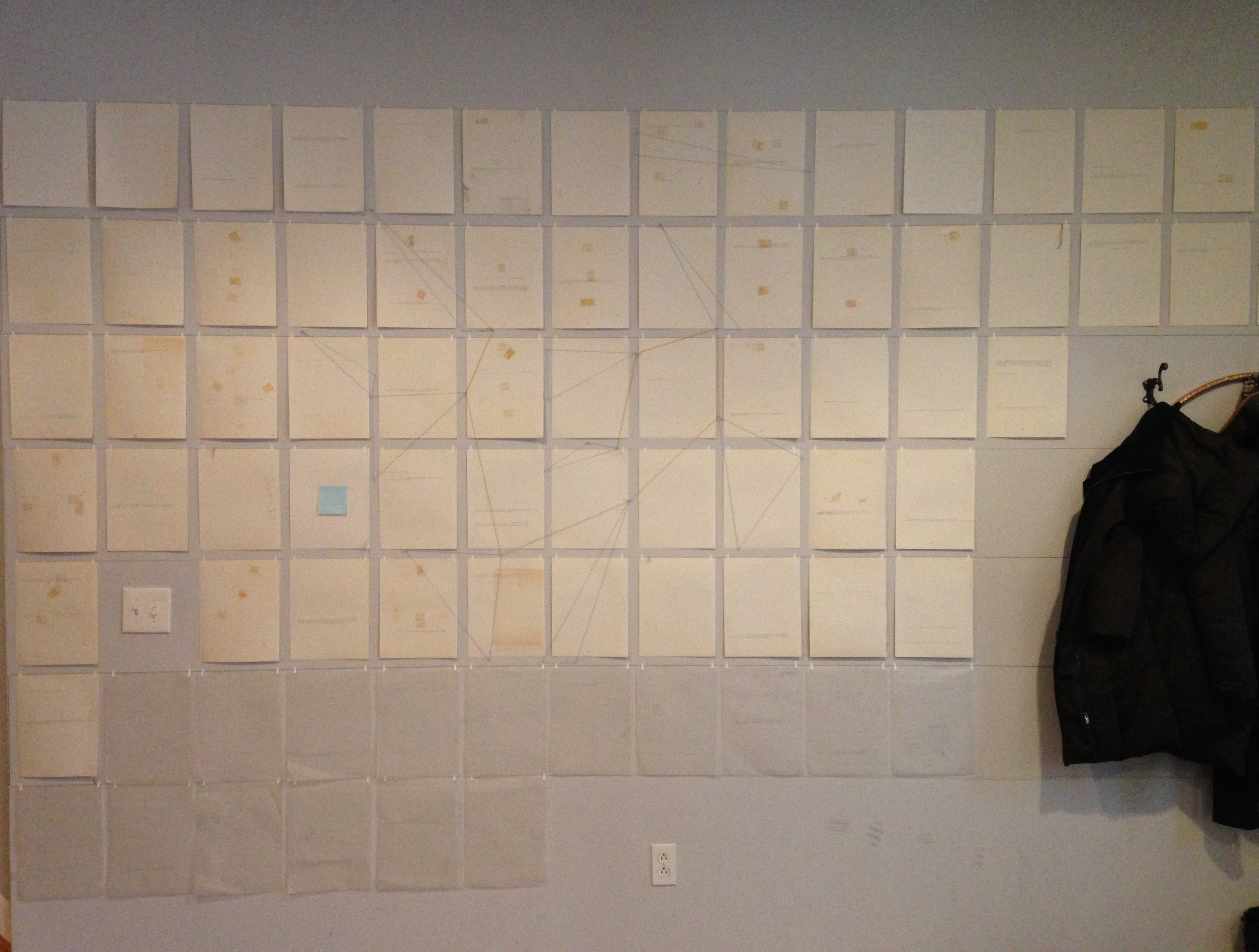

When I finally returned, I came home to find an entire wall of our living room covered in individual pieces of copy paper, lined up in rows creating a precise grid. Each page, though mostly empty space, contained a hand typed phrase tucked into a corner or spread across the top of the sheet just below where a margin would frame a block of text. Or, sometimes, a nearly blank page was dotted with singular words, now seeming to reach toward each other for context and meaning across the divide of empty space.

The more free it is of its own inner contradictions, the more whole and healthy and wholehearted it becomes.

self-maintaining

self destroying

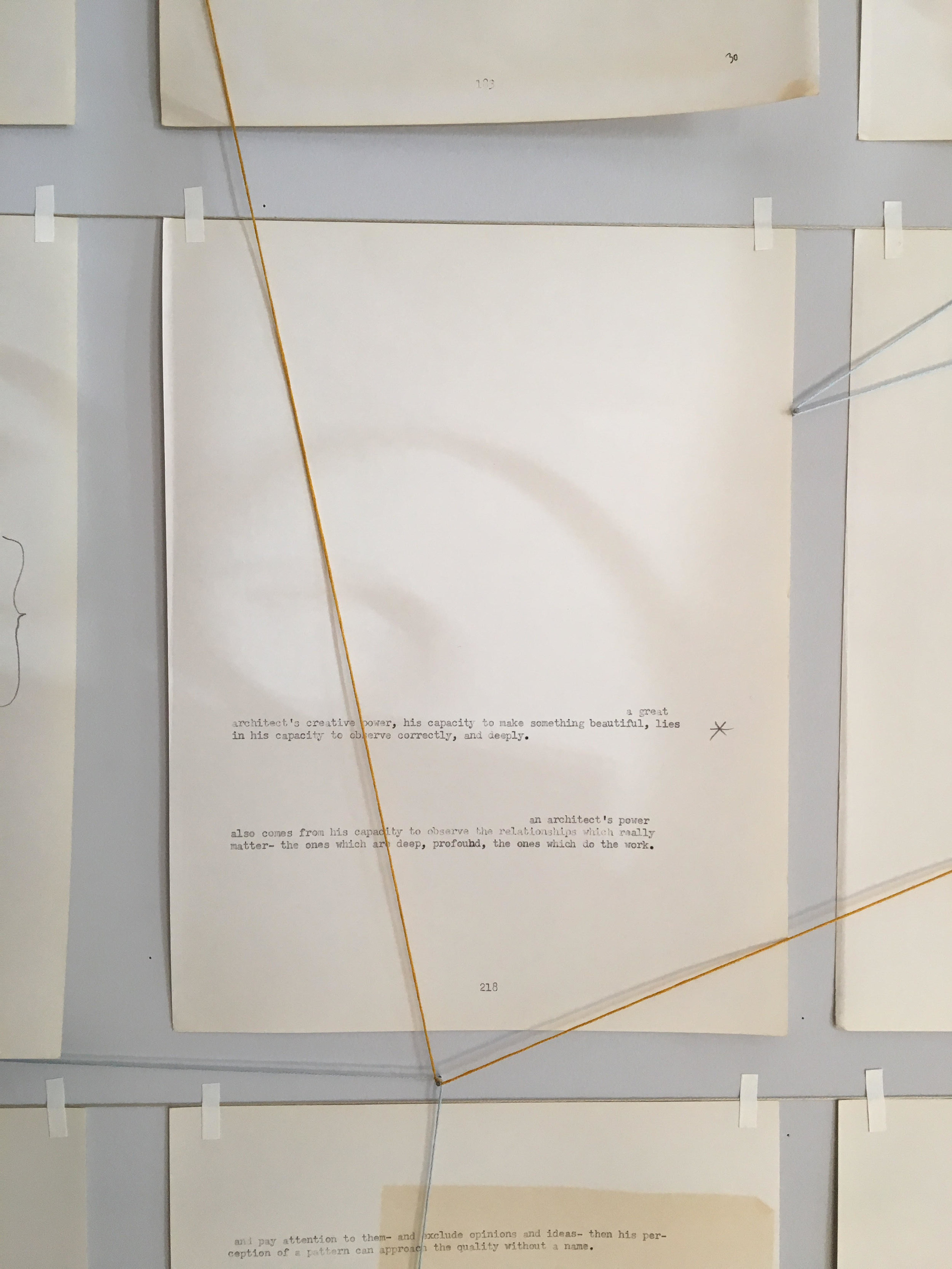

I recognized the phrases immediately. Owen made an abridged edition of one of my favorite books, The Timeless Way of Building. The vast empty space represented the bulk of the book, and the phrases she transcribed with her 1950s quiet de luxe typewriter were the portions I had underlined. The Timeless Way of Building is an architecture text book equally beloved and scorned for the way its building instructions read more like a volume of Taoist poetry. As I scanned the wall for text, each familiar quote brought me back to the time when I first read The Timeless Way, a time when, in the midst of a pileup of personal losses, I was wondering what was next.

The greatest fear we experience in the process of design is that everything will not work out. And yet the building will become alive only when you can let go of this fear.

Now condensed into only my favorite phrases, this ultra refined edition becomes odd sort of cliff notes, useful only to the small number of people in this world who are interested in my particular version of things. Perhaps, in fact, useful only to me.

This project reminded me of one of the less accessible suggestions from the quietly weird and wonderful book,The Life-Changing Magic Of Tidying Up. For those who have yet to join author Marie Kondo’s cult of declutters as I have, the author outlines a rigorous process in which you systematically go through each item that you own and make a conscious decision about whether to keep it or throw it away.

Although unfailingly devoted to her project, Kondo gets stuck when she arrives at her book shelf. What about books that do not belong in her “hall of fame,” as she calls it, but still do have some value? She runs through ideas about how to keep what she does love without falling short of her own meticulous standard of complete clutter eradication.

To resolve the issue, she first tries recording her favorite parts of each book by hand into a notebook, but soon decides the method is too time-consuming. She then tries photocopying each page, but this takes even longer. Eventually, she settles on a method of tearing out the best pages and storing them in a folder. “This only took five minutes per book,” the author explains, “and I managed to get rid of forty books and keep the words that I liked. I was extremely pleased with the results.”

Extremely pleased. While some have criticized Kondo for promoting Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, my only complaint is that she stopped just short of the final treasure of her deep obsession. A loose collection of full book pages would inevitably include several excess phrases as well as sentences once spanning two pages now chopped in half. But, her initial proposition: a notebook filled with only every beloved word, leaves me with the image of an incredibly satisfying compendium that would transcend each individual author’s voice to become, instead, a composite map of the book owner’s mind.

Kondo’s quest recalls another of my my favorite books, The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, Thomas Jefferson’s private volume which he constructed by cutting and pasting passages from Greek, Latin, French & English New Testaments, leaving only phrases that represented his preferred perspective. Although reprints are now available, this ambitious and beautiful object was only shared among close friends during his lifetime. In letter to John Adams, Jefferson explained the project stating “I have performed this operation for my own use...” I love imagining the painstaking hours spent by candle light, slicing up Bibles with a razor blade to bring his private vision into existence.

Admiring the completeness of Owen’s book project, I noticed that even the hand drawn asterisks and brackets were included, reproduced in pencil marks around the edges. While most of the phrases and marginalia were instantly familiar, a few stuck out to me as odd. One note in particular highlighted the difference between common building materials, sheet rock and plaster. While the book contains immense practical advice for designing and constructing buildings, I was drawn to it for the metaphors that emerged from the author’s instructions.

Curious, then, about the unfamiliar notes, I opened up my copy of the book. I found the mysterious handwriting and remembered that, after I was finished reading it, I lent it to the man I was dating at the time who happened to be in the process of renovating a building.

Looking over his notes in my book for the first time, I was flooded with memories of summer nights perched in front the second story window of his building, watching the sun set over a garden below. I remembered the way he described the vision for this old brick structure, with its crumbling facade but solid bones. I had wanted to help, so he taught me how to properly restore brick and we would work side by side late into the night, discussing music and art and The Timeless Way of Building.

Books are a way of knowing and being known, a gentle invitation inside the mind of another. They offer a new perspective, or, sometimes, the rush of recognizing your own innermost thoughts articulated even more precisely by someone else. Connection. To me, underlining and making notes is a way of participating in the exchange.

Now the mysterious marginalia made perfect sense. While I was drawn to The Timeless Way of Building as a guide for rebuilding a life, he was actually making a building. Another character was added to the conversation across space and time.

***

Where other obsessive types like Marie Kondo and Thomas Jefferson have gone to great lengths to create such a volume for their personal edification, Owen’s project is distinct in that she puts all of her attention on the mind and home and habits of someone else.

In addition to her book project, Owen collected dust from around our space by pressing packing tape into corners of the hardwood floor and behind bookshelves. Then, she folded the packing tape in half to contain her specimen, and placed the enfolded samples into plastic slide frames, filling the cartridge of a slide projector. Now enlarged and illuminated by light, these bits of stray down feathers, twisted staples, swirls of hair and fuzz, and crispy leaf fragments become abstracted shapes as they clumsily cycle through the slide cartridge like a Stan Brakhage film in slow motion. Owen performs a strange sort of cleaning service, excavating worlds and subtly revealing the patterns of the people inhabiting her chosen spaces, as a forensic scientist reveals fingerprints. Owen’s collected material occurs as evidence, but evidence of what?

These glowing images speak to the tangled intimacies of lives overlapping, and to the ways shared spaces hold these stories. Bodies leave a trace. Watching these slides slowly rotate is like noticing a stray hair on your pillow entangled with that of your partner after they are gone.

While watching these slides cycle through I feel studied, examined. It’s as though Owen is looking for answers, but the questions themselves remain hidden. Although the forms of her work reference the language of academic or professional presentations with their grids and circulating images, the information itself manages to escape definition. As I observe these flickering mementos of my existence, I am left with the feeling of being haunted, but the ghost, it seems, is me.

All of this close attention is carried out with such tenderness that what could feel like a voyeuristic imposition, feels more like falling in love. Specifically, her process invokes the moment when interest is expressed and there is an invitation to reciprocate. Suddenly someone puts attention on your inner world and wants to know how you think, how you move through space. What seems ordinary and forgettable about your own existence becomes animated with the curiosity of another. Is it possible that all the annoying little things about you could be accepted, or even celebrated, by another human being?

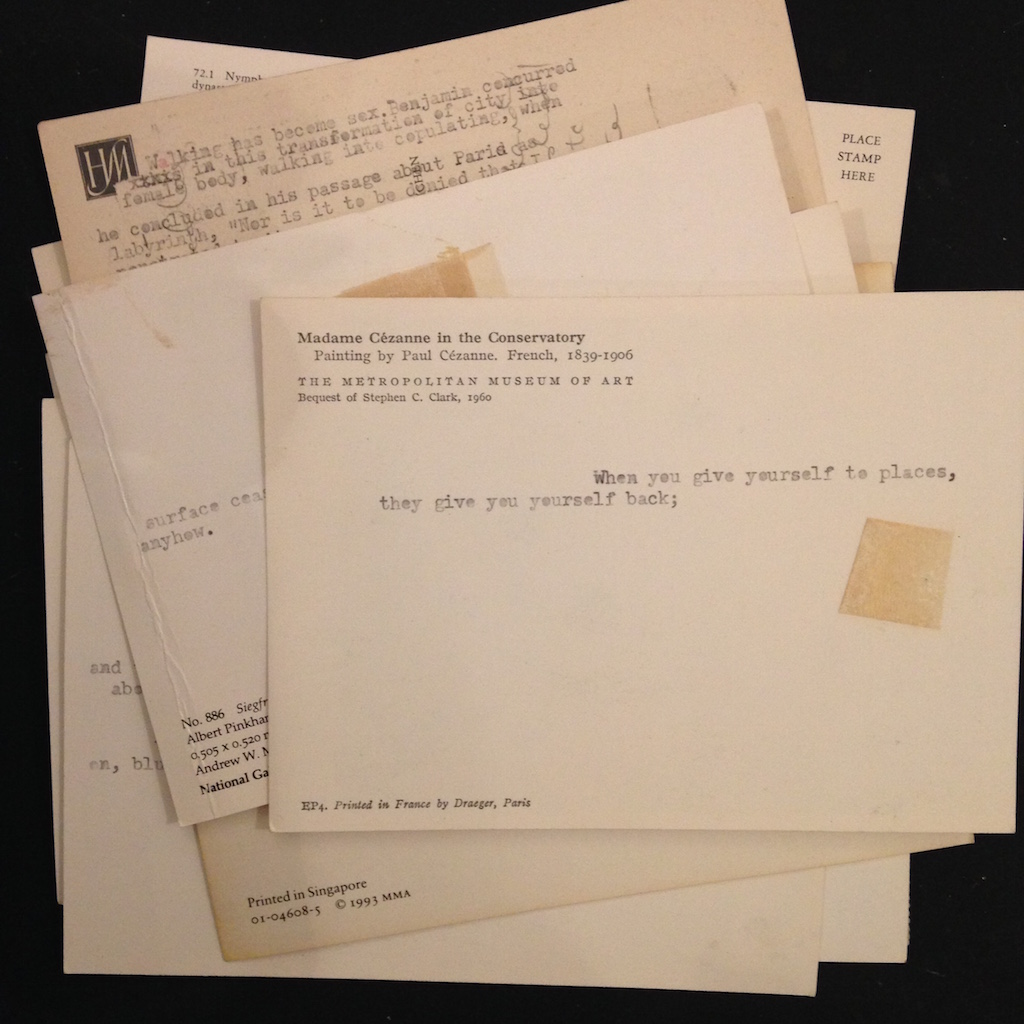

While I was away at the silent meditation course, I had an experience that I imagine is common in such settings: moments of feeling so full of love I could drown in it. As I considered what to do with this towering affection, an idea came to me that I would send gifts and letters of appreciation to my friends. I was amazed, then, that in addition to returning home to my favorite passages from my favorite book splayed on my wall, I also found these passages and others from my book shelf typed onto vintage postcards. Owen invites her audience to sift through the stack and, if a quote reminds them of someone they know, to fill in the address for her to send along in the mail. My dream of radiating my endearment through the postal service suddenly increased ten-fold, as quotes from my favorite books now trickle out not only to my friends but to friends of friends, including people I have never met and likely never will.

All of these works use the language of archives, places where things like notebook paper and old polaroid prints are granted the same status as hand-bound, hard-covered books with gold lettering pressed into red leather. This elevation of the mundane reflects a childlike perspective of the world in the best sense: a quality of imagination that turns a broken cup into a tea party, and a stray feather into an elegant quill pen. With my most beloved passages from my favorite books now circulating, and with the detritus of my daily life glowing and enlarged, I am reminded of the temporarily collapsed boundaries of falling in love, and the resulting expanded image of oneself from the gift of being viewed in exceptionally generous light. And, as with falling in love, after the dopamine fades, what you are left with in the end is a reflection of yourself, looking into the eyes of an ordinary human who is shimmering beyond their own limits with the halo you have placed around them.

Alison Owen is in love with you. And I am, too.