Drinking Forever: Lessons in Lemonade for a Black Mother and Son [shawna floyd]

Raising Black children – female and male – in the mouth of a racist, sexist, suicidal dragon is perilous and chancy. If they cannot love and resist at the same time, they will probably not survive. And in order to survive they must let go. This is what mothers teach – love, survival – that is, self-definition and letting go. (Audre Lorde, “Man Child” in Sister Outsider, 1984)

[Black people] need to recover the legacy of resilience. (Dr. Catherine Meeks, in a book talk at First Baptist Church of Decatur for her co-authored book with the reverend Nibs Stroupe, Passionate for Justice: Ida B. Wells as Prophet for Our Time, September 24, 2019)

Give a man a fish, and he'll eat for a day. Teach him how to fish and he'll eat forever. (Arrested Development, “Give a Man a Fish” on 3 Years, 5 Months and 2 Days in the Life Of…, 1992)

Beloved Son,

I am afraid that my mothering powers will not be able to reach you in California.

I am afraid that this once-poor, erstwhile-single, scrupulous black mama magic...

Well, that it's too much to ask.

That it's too much to ask of it.

I am afraid that this

intergenerationally-poor

intergenerationally-single

scrupulous

black mama magic

can suffice when you are near me

but may come apart

when you go.

My right eye has been twitching for weeks.

Where it had once been

steady

reliable

potent

it is now flickering like a candle flame giving way to the winds.

All that I have cobbled together

all the cardboard boxes turned playhouses

all the thrift store bric-a-brac I washed and polished and alchemized

with a poor black mother's love

all the park visits turned safari

all the library books turned airline ticket, escapade, getaway

all the beans and lentils and rice

all the costs I learned to sidestep: school pictures, for instance...

Do you remember the times when we'd put our bathing suits and rain boots or bare feet

on and go splash about in the rain?

All the bright, whimsical places I took you to

that we could afford

so that you did not know anything about the targets on our backs?

The children's section in the bookstore.

The pool with the free swim between 3:00 and 5:00.

With the lazy river that carries you into a whirlpool.

The nature preserve with that observation deck

that would never be named after some unwittingly-poor black boy

whose middle name is observation, thank you!

That nature preserve whose creeks delighted you with tadpoles

whose little beaches you explored for something in particular that you nor I

can remember.

That nature preserve where your sister got stung in the eye by a hornet.

That nature preserve where we picked blackberries.

Oh what a pretty piece of cloth can do:

cover a weathered second- third- fourthhand table

substitute for curtains

turn a bulletin board into framed art

or leave it a bulletin board but

soften the call of the duties from that board

line dingy shelves

armor a black mother's head and mind.

All the lemonade I've made from the sour

of abandonment

of deprivation.

Does the recipe travel?

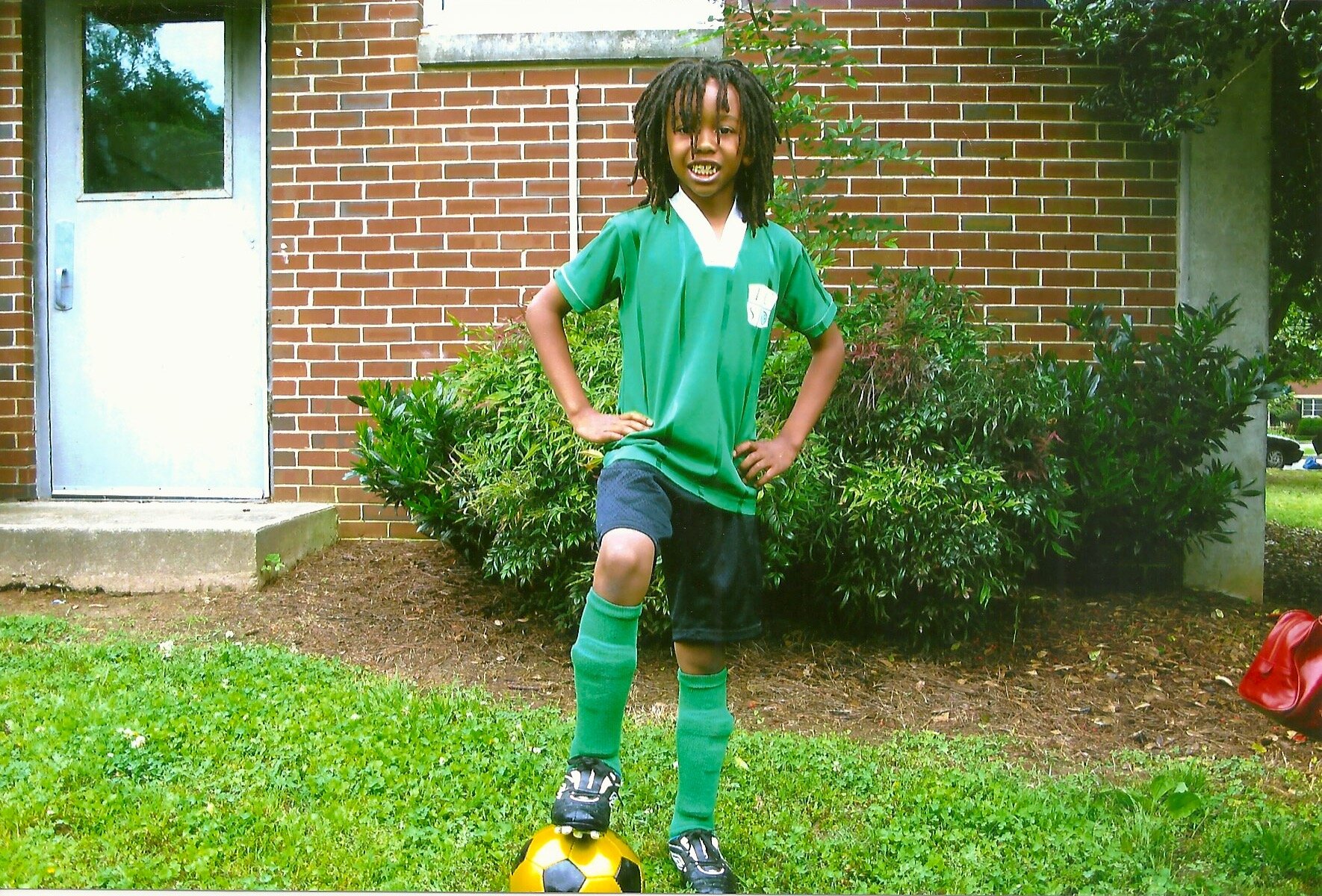

The main ingredient is me. The conservancy of my body. The sanctuary of my love. The poor, single black mama (emeritus now) as *a body concerned with the preservation of nature, specific species or natural resources. The hands that maintained your locs for almost a decade. Same hands sheared them when you were tired of being mistaken for a girl, when you were exasperated with people's superficial associations (you look nothing like Lil Wayne), when your tenderheadedness made the final call, when your introversion softened and you were ready to get the hair out of your face and allow observation both ways. These guilty conservation hands that smacked your sister when she sprayed Shout in your eyes. These breasts that fed and consoled you. This body that still situates itself between you and traffic even though you are now taller and more muscular than me and are just seven pounds shy of my weight—at least, that was the case when you left here. The body that fills in the space beside you at orientation, at curriculum night, at the movie theatre, at the pediatrician's office, at the wherever. The body that means you are attached, moored, secured—that you will not be loosened or taken from or lost to those who love you. We will not be undone. This is a body that presents itself spurred by bodies before it that meant to be the same kind of nurturing, protection, warning, preemption, enhancement, accomplice in freedom. My body as your accomplice. How will I be complicit on the other side of the country? What will I do without my body, my presence as preemptive strike?

Even without locs draping your face—seven years they've been gone (eight years now at the time of publication)—you are still like a window with the primary curtains partially drawn and the sheers ever present. But, sometimes, often enough for me to know you, when we are together you are barepane-faced...but, really, you are a house. So, sometimes, often enough for me to know you, when we are together you let your curtains and sheers down and barepane-faced I can see into your rooms. It can be hard to know what goes on in your house. You are not like your sister, who is like y'all's mama: a naked dweller-dancer in a curtainless house with the doors flung wide (at least a good deal of the time). It seems to me that it has been our proximity to each other that has facilitated my welcome to view your rooms—and sometimes to step inside of them, and sometimes to have a seat, and sometimes to make myself at home. You are not much of a phone talker. It seems to me that it is when we are within the precinct that is us that you habitually unfurl. When we are in other districts, you are rolled up. Are we still a precinct when we are not physically proximate? When you can not saunter into whichever room I've taken up with to write first thing in the morning; when you cannot look out of whichever window and start unfolding your first words of the day, talking to me with your eyes first somewhere else before they meander to mine; when you cannot drift your way to confiding in me, sharing your anxieties, your furies, your hopes...What will we do? What will I do?

She armored herself for battle in pumps, a suit, a briefcase and a crisp, calculated off-wit-yo-head Queen's English formed by lips ablaze in Fashion Fair lipstick.

Will you call? To not know you in this world unfit for you is a danger. To not be close to you in an unregenerate America puts my nerves on a different edge, the edge across from the one that my nerves are most familiar with: being close to you in this place that holds similar and different dangers for me. But being close to you, nonetheless: close enough, one time, working from home, to leave my laptop to address the police officers (one black man, one white woman) patrolling our neighborhood after a series of incidents, who stopped you on your way home from the bus stop. Did they ask you if you knew the suspected youth because you are, also, black? It doesn't matter. I took this body, a descendant of others just like it, and injected and introduced myself (read told them that you are loved and watched over—and so are those suspected youth). I am familiar with that edge of my nerves when you are nearby. I am close enough to take my flint of heart black mama self up to the school if those striking their steely words and ways on my child want to try me. I am like my own mother (the grandmother you may never meet) in this way. She armored herself for battle in pumps, a suit, a briefcase and a crisp, calculated off-wit-yo-head Queen's English formed by lips ablaze in Fashion Fair lipstick. My father, your grandfather—before my parents came brutally undone (and it didn't take long)—would come, well, packin heat. My defenses are mine. You know their array. From lipsticked gangster to namaste. I know something about how to mother you in and through spaces unworthy of you. But I've always been close: close enough to plant hugs on and in you, to be near when you sprout hugs so that they don't wither on the vine, close enough to steer you, to see the fresh pimples on your back, for you to see the vernacular animating and adding dimensions to my communication, close enough to chide you about procrastination, close enough to sense your anxieties, close enough to see your face slip out of its cool imperturbability into relieving laughter, close enough to hand you something you need, close enough to catch a bullet, close enough to wield the fullness of my powers.

But this was always going to happen. I was always going to have to love you and turn you loose. I was always going to have to love you and turn you loose in this place. How have mothers like me done it? Even now, the day before I fly with you to what might as well be the other side of the world, my mind is churning, sifting: what do I need to say and do these last few days we will have in each other's presence for months? Is it too late to make a handbook? Recite back to me the protocol for when you are detained by a cop. Do you have the card for that kind white lady in your wallet? You know! The attorney who said to call her if you ever get arrested? She practices here in Georgia, though. Still, keep it on you. You never know.

There is the industrial strength racism like the kudzu I've seen strangling trees on my job around our city. "The vine that ate the South" is a fitting appellation⎯especially if one agrees with the view from Malcolm X's black-rimmed spectacles about where "the South" is.

Should I tell you about that time I got detained (but eventually let go) because I was in the car with my friend when they were buying weed? Should I tell you about the time a different friend of mine and I almost got caught buying weed but a timely "hootie hoo" and the fast driving of my friend helped us escape arrest? Should I tell you the long story about the time I, surging with adrenaline, had to defend against the unwelcome sexual advances of the drunk brother of someone you know? Should I tell you the long story about how I got pregnant—was that at eighteen or nineteen?—by the supervisor at my job and had an abortion? Should I tell you more? Should I just tell you that I love you, that I'm proud of you, that I'm excited for you?

I haven't said enough about breathing. You know that feeling when you're stressing out and you're holding your breath or your breath is shallow and your body is tense? No? Well, never mind, then.

There is the industrial strength racism like the kudzu I've seen strangling trees on my job around our city. "The vine that ate the South" is a fitting appellation—especially if one agrees with the view from Malcolm X's black-rimmed spectacles about where "the South" is. Can I get a witness. No question mark needed. The racism that saliently coils and smothers and chokes and leaves in its wake the stuff of nightmares, of horror movies, of real life: giant, ruthless monstrosities with no respect for life or limb or liberty or the pursuit of happiness of "others," a construct to justify eating up everything.

A pretending that we are plastic

dolls with smiles but no mouths

abdomens with no stomachs

heads with no mooring

unfinished things

that have no rights

"which the white man [is] bound to respect"

or

for the liberals and progressives out there

that we have no experience

of the denial of rights

that warrants immediate redress.

Hungry people

who can't eat

can't afford incremental change.

Death by a thousand

delays

a thousand

conservations

a thousand

civilities

a thousand

bail outs.

Racism

like the banks

too big to fail.

If justice was their aim, hand wringing and excruciating and the staking of yard signs would not be appropriate ways to respond—and keep responding. And don't let them fool you: It does matter de dónde eres. The descendants of enslaved Africans have had housing policies pointed, aimed and shot at us to keep us from being their neighbors—and those attacks have had a lasting effect (see gentrification). There are no such signs welcoming black americans to the neighborhood. Maybe in the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. But don't be black and gay. Please refer to Won't You Be My Neighbor?

The only way I can get with those Racism Sucks tee shirts is if this is the kind of sucking to which they refer. The killing kind.

There is

racism like whiteflies

concealed in a congregation

under a plant's leaves

feeding on its juices. Weakening the plant. Wilting and yellowing the leaves. Thwarting photosynthesis. Stunting its growth. The only way I can get with those Racism Sucks tee shirts is if this is the kind of sucking to which they refer. The killing kind. Otherwise, euphemisms and racism don't mix.

I dropped you off in a town where the only black people we saw the first day were our reflections accompanying us through the town in storefront windows and doors. When we sat down to an early dinner in a local restaurant, I almost jumped from my seat near the restaurant's window to bolt out of the door to follow and make the acquaintance of whom I thought was a black man hurrying by. He was going too fast and I was limp from travel and meal hunger. I question if he was black now, because there were multiple times in that city when I thought I saw a black person from afar but for my faculties to register, instead, brown (and probably not Latinx) up close.

Everywhere we went in the town, everyone was nice. Some were kind. I make a distinction when I'm being precise with my words. Both of us remarked at the patient, unrushed, respectful-of-pedestrian practice of motor vehicle operators approaching stop signs: the wide berth, the unhurried approach of the stop, the backing-up to accommodate our crossing. And yet I grew sticky with gazes. And I began to wonder if the idyllic appearance of this place had any correlation to what seemed like an absence of black people. And like a nictitating membrane, I drew a barrier-preserver across each eye, across myself, as I am accustomed to doing around nice, smiling white people who are living free of black people. I tucked certain parts of myself away for safekeeping cuz white people will say and do the darndest things—especially around certain black people. Please refer to the first episode of Atlanta.

Ever since we found out the head of school at this art-centric boarding school was black, and tightcurl-headed, I knew that once we got to town I could ask him where you could get your hair cut. You and I laughed with specificity and relief upon the discovery. Then, later on, I found out that there was a new head of school. Shit, I thought. I was tearing through the new head of school's biography on the website. I came to his picture: a black man! What does it mean to not be able to take for granted that your grooming needs can be met in a place where you will reside? When we were packing for this trip, I thought that someone should do a sketch comedy piece—if they haven't already—on how these TSA liquid and gel restrictions are racist. I'd have it show happy-go-lucky white people with their wash-and-go, we'll-just-use-the-hotel-products, there'll-be-a-blow-dryer-awaiting-us, light-packing selves breezing through TSA security with no storage bag of liquids and gels needed. I don't even care to follow the sketch through to the depiction of black people going through security check. My mind has jumped ahead to hotels making shea butter and black hair care products standard in the room and complimentary. Just like if you forget your toothbrush or toothpaste, you can get issued a headscarf gratis to sleep in. Or some bump control aftershave. I didn't see nary a shower cap in that bed and breakfast we stayed at. Guess that's some extra, out of the ordinary type shit for some folks.

...a barbershop's storefront with a name that formed the plural with a "z"! Saved!

After we ate dinner that first night, as I'm sure you remember, we went to scope out the school the day before orientation. And like five minutes away from the school (three minutes?) I saw it: a barbershop's storefront with a name that formed the plural with a "z"! Saved! Through the glass: Brown! Latino? Latino! men cutting hair; antennae activating...one Afro Latino? cutting hair, brown men, Latinos?! in chairs. Saved! But still I had to ask (just to make sure), and you knew I was gonna do it, I had already primed you, you knew that after we stepped inside, after I introduced us, after I explained our presence in the city, me standing eagerly steps ahead of you, in all my black mama earnestness, I had to be sure, so my voice asked: "Do you know how to cut hair like my son's?" My antennae asked: "Can I leave my son in this place?" "Yes," they smiled and said. And one man in particular came out to reassure me—after we had gotten a business card, the IG handle and the business hours and had stepped back onto the city sidewalk. The owners hail from Honduras, he said; he was related somehow? am I making this up? by marriage or something, I don't remember; he grew up in this town; it was not diverse when he was coming up; it's getting/has gotten better; someone from the school—a black man—came to get his hair cut recently (has to be head of school); his husband was with him (yeah, it was head of school); proof that the shop welcomes everybody, reassured this Latino brotha.

Gps says that I am a one day and twelve hour car drive from you, son. But you are a four minute walk from the barbershop.

When we were both much younger, there was this day I was steering us (you were in a carrier hanging from my back) through a New York City sidewalk. "That's dangerous," said a voice from behind me. Adrenaline pinballed through me as I turned to address this voice of caution that some other evaluative part of me did note was not ominous, per se. My eyes located the owner of the voice. She was smiling, delighted, delighting in your deliciously "dangerous" bare swinging baby legs and feet. You and your sister like to tease me when babies come into my orbit, now: "Mama, don't lick the baby!" you joke. Your sister sends me random text messages with images of chunky-cheeked, bow-mouthed black baby candy to pretend to send me into a frenzy. We're all tickled by these antics. And, sometimes, I think of that lady.

From the vantage point of nearly eighteen years of mothering (eighteen years and counting now at the time of publication), I recast the memory for my purposes. Was the danger that your creamy golden legs and feet and toes would send folk into a frenzy, possessing them to steal a pinch? Or, is the danger a moth to a flame variety, asks the weathered twice-poor, twice-single mother of two? Like a moth hovering near a flame, I oo and ah at the random fires ablaze in your sister's tantalizing texts, the chance fires at the grocery store, on the streets of Atlanta, the anticipated ones in the homes of friends and family. Like a mother who loves children, I warm my hands by these fires. Like a woman who loves herself I keep my distance, hold on to my growing wings.

I wonder what that white woman would feel if she were walking behind you again on the sidewalks of New York, but with you, this time, on your own two muscular legs, your pull-up defined arms hanging out of a graphic tee, me nowhere in sight. What types of frenzies do people go into when they see your body now? What types of dangers do people associate with you now? People used to encourage me to get you into baby modeling. "He should model. He could model for BabyGap." Can you move through this world with neutrality? There is more to a black man's existence than a volley between compliments and condemnation, exaltation and exclusion.

Be careful of the seduction of praise. I understand the draw of Black Cool (aka Cool, period). If nothing else, we cool. We are style. We are grace. We are art. We are impossible. We shimmy from a shambles. We shimmer from a shambles. And everybody wants it. The shimmer, that is. Eighty-six the shambles. That shimmer sells soft drinks; it sells cars; it sells makeup; it sells Apple watches.

A song

about black liberation

used

to sell Apple watches.

Neutralized. Again.

But folks is gettin paid.

I get it.

And I get

that the individual pursuit of money is not justice.

Justice has no substitute.

Plus, have we not been instructed/cautioned that "the revolution will not be televised"? (Do you know this Gil Scott-Heron song?) Capitalism is revolution-resistant. Advertisers are pushin product. They will "Fifteen Million Merits" that shit with the quickness. R-e-f-e-r t-o B-l-a-c-k M-i-r-r-o-r is being typed on a refurbished MacBook Pro. I'm still of this world. I just know that the revolution will not be brought to me by Apple.

But back to black people and our shimmer. The shimmer adopted by people who are not black is all the rage. I get it. It has no match. It enriches their vocabulary, enriches expression itself. It leavens what is flat. Brightens what is dull. It confers (with no conference) cool. And, once in hand, it is used to sell whatever is being sold. It sells their films—even if they're devoid of black people. They don't need a black comedian-actor grounded in the heritage of black humor to enliven their films. Appropriators abound. Neck rolls and accents and tones and hand gestures and nomenclature and the like proliferate. See fill-in-the-blank, take-yo-pick film. Black culture is treated like a commodity

transferable

public domain

the nappy-headed step-child

of America

with a gold mine mouth.

*Step-, from its Germanic origin

bereaved, orphaned

as in

*be deprived of a loved one through a profound absence,

especially due to the loved one's death.

Black culture

and black people

are not deprived

of loved ones—

although attempts

were made

and continue.

That is the lie.

One of many.

Shim shimmer. Who's got the keys to the shimmer?

...there is no rising curtain to animate or falling curtain to deanimate blackness. It's not an act.

This shimmer grafting is a relief from the buttoned-up, itchy, fogeyish whiteness that certain white people everywhere are trying to abandon while keeping all of whiteness's perquisites. This shimmer tourism can be a kind of being in Rome and doing as the Romans do, or, said another way, being in the world and doing as the Black Americans do. Holler if you hear me. Folks trying to follow the customs of the Shimmerers from a Shambles. It is a compliment, sincere and backhanded at the same damn time. It is deferential: rustling up what French you know to speak it to the French in France. It is a surrender: rounding up what Black English you know to speak it in a world mesmerized by capital B Black capital A Americans or versions or parts or legends or _______ of us. It is also a carelessness and a carefreeness. It is also an exploitation. It is... Whatever it is, it has been adopted like a black child by a white family in which nobody knows how to do that curly black hair—or even, alternatively, like a black child adopted by a white family with members who have done their homework, their research, the tutorials, who know about greasin scalps and cornrowin. That is to say, whatever the case may be, blaccent-, AAVE-adopting people (white or not), folks adopting our styles and ways (for good reason or not) ain't black—whatever their proximity to blackness or attempts to approximate blackness may be. And these advertisers and their urban or multicultural marketing teams aren't producing black culture: let me go ahead and untwist that so that it can be foreva untwisted. No matter if Dontavius or Shakeeta head the team. Who you are, who your people are, where you come from, where you're going can't be packaged and sold. It's not a costume. It's not a safari. And while there are aspects of our culture that can be choreographed, orchestrated, performed...there is no rising curtain to animate or falling curtain to deanimate blackness. It's not an act. It's not this narrow Black Cool being flaunted and touted and exploited everywhere. Black is cool. Black is cold. Black is warm. Black is hot. Black is all the feels. But Black is not superhuman: they need to stop it. And Black is not subhuman: they need to quit it. Black is human. Always was. Always will be. Whether we name ourselves black or anything else. Doesn't mean we ain't fly. Just means we are also crawl. And some more stuff. Let's not let the Architects of Shambles have us reacting to and replicating their smallness. Their binaries. Their shackles. That fuck shit.

And if I didn't tell you:

Son, I want for you what I want for myself: to get free, as fast as you can; to be free; to stay free.

We don't need to pretend invulnerability. That is not the answer to brutality. It's resistance.

I have had many years on many an occasion to consider the much-quoted words of Audre Lorde: "the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house." It wasn't until recently that I interpreted tools as not just beliefs and practices, but as actual selves. I find it useful (for a pair of poems I'm working on and for living life) to apprehend people (including, and especially, myself) as the tools, as having been smithed into tools to facilitate the ends of the masters/the rulers/the dominators—to be the tools of what bell hooks calls the "imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy." I find it essential to recognize the crucible in which I was/we were formed, misshapen, set (let me mix my metaphors), like jewels, against ourselves. When I say "we," it houses a multitude. The very house Dr. King referred to when he, horrified, (sooth)said that he might "have integrated my people into a burning house." Everybody up in that house, that infernal inferno, has been cast, has been molested, interfered with: is fucked. White people, too and particularly. Everybody. It's nothing to be ashamed of, son. We don't need to pretend invulnerability. That is not the answer to brutality. It's resistance. Dr. Catherine Meeks, who is the Executive Director of the Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing, says we must "commit ourselves to being resistors" and that "You should always be disturbed by your lack of resistance." Resistance is different from acting all hard, take note. The answer to inhumanity is humanity. The resistance to inhumanity is a humanity that will struggle for itself, snatch itself back from the workshop of cruelty (and the world is inhumanity's workshop—and the world is humanity's workshop). Humanity will re-form itself in the fires of tenderness, of compassion, of fierceness, of love, of justice. It will pop itself out of the ruler's crown, like a head escaped from a spike to reconstitute itself (a new constitution!), unkilling itself, shimmying from a shambles. We, the people, must do this.

They are not our proxies.

I want you to know that rich, black, celebrity people aren't coming to the rescue. And if we're not careful, they can be used like Christianity was used against our ancestors and us: to have us looking outside of our own selves and our own lives for a savior and a promised land. When fill-in-the-blank rich, celebrity black person is eatin, our bellies don't get full. When they whippin around in they cars on cars on cars, it don't keep our car from overheatin. They are not our proxies.

I want you to know that you can have an abiding love for our people and, simultaneously, not be naive about the crucible in which we have been formed and about the damage caused to our people by these reinforcing systems of domination. Hurt people do hurt people. You learned this well on the bus, on the playground, in gym class, in the world of children. And that is why I think that recovering ourselves from the shapeshifting calamities of race and racism is foundational liberatory work. And, yes, race is a calamity, too. It is not a neutral construct. It's a pseudo-science technology. It's a weapon. Refer to Karen E. and Barbara J. Fields’s Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life.

I remember you, son, at tenderer ages, before you armored up to survive the prevailing world of boys and men.

I want you to know that there are men who and constructs of masculinity that are not toxic. Don't let the men who have hurt and disappointed you have the last say about masculinity. For you are a young man, masculine, yourself—and you are not condemned to reproduce hurt and disappointment and selfishness and greed and brutality and domination, if you resist, if you love, if you are just. Read some bell hooks, find your kind of menfolk and recover masculinity from those who degrade it.

You already know that there are some radical white people out here who ain't restin on these perks. When I was growing up, I didn't know such a thing could exist. And still, white supremacy, inherent from the inception of this country, where you were born and raised, and where I was born and raised, and, shit, where my parents were born and raised and their parents were born and raised and their parents were born and raised and where we have been living and building for longer than a significant number of these white people who live here...my goodness, it snaps you to attention... My point: white supremacy makes all white people shareholders. They just don't hold equal shares. Hear "Fortunate Son" by Creedence Clearwater Revival.

America does not have to stay stubbornly, resiliently wrong.

If anyone tries to tell you that some white people don't got no perks, you don't have to tell them a gotdamn thing, if you don't want; just aim your attention to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice (aka the National Lynching Museum⎯thank goodness for informal names) and know that freedom from racialized terror is a muthafuckin perk. The not being deemed the foil and antithesis of white in a brutal racial hierarchy, the not being regarded as the bogeyman of America is indeed an advantage. I used to half-joke that all black people needed therapy (we done been through so much)—and that it should be free—and then I discovered Joy DeGruy's work about our intergenerational trauma. Yo...just read it.

My great grandfather on my mother's side used to talk about his mother? grandmother? being Indian. Recently, my dad shared a memory of his grandmother speaking of Blackfoot Indian in our lineage. I've never looked at this information very closely. I don't know if it's accurate. (Sometimes I wonder if black americans would rather explain our sundry skin tones and hair textures and other phenotypic traits with claims of indigenous ancestry rather than European ancestry fraught with the history of rape and its proceeds.) But these stories and claims of indigenous lineage stay with me. So far, I haven't been the kind of person seeking to know the fine details of my ancestry—indigenous, African or what have you—even though I acknowledge what I know and what I've been told. Being black american has been such a thing unto itself, in many ways. I see it as once a part and apart. And it is the culture with which I have been imbued. Still: what would my great granddaddy's mama? granny? (if she was indigenous) say about white supremacy and her—our?! other—people's living and building here?

America does not have to stay stubbornly, resiliently wrong. And whether it does or not, don't you, son. Say sorry when you're wrong. And repair the shit that you damage. Try, at least, to make things whole. Do right by people. I have this concept of little j justice and big J Justice. They are not in a hierarchical relationship. Little j justice is "little" in relative scale to "big" J Justice. Practicing justice in a mother-son relationship is the craft of little j. Social justice is the work of big J. Little j has no shorter reach than big J, if you think about it. And little j justices are the building blocks of big J. At least, that's the way I'm beginning to apprehend justice.

Did I think I could somehow be like the Pansy Patrol at the Atlanta Pride parade?

Son, I cannot get to you quickly. Do not hesitate to reach out to your roommate's mother, that local mama of color who (if you noticed) extended her home to you even before she and I sat down and had Mamas of Color Corner/People of Color Conference on the couch outside of the room that you and her son share for a semester.

I want this letter to do what no one letter could ever do. I know.

I am trying to have you cram before the examination. But you're already gone. And I already raised you, didn't I? And, also, it's not like I'm done being your mama.

Did I think I was gonna remove the sour from this world? No. Did I think I could somehow be like the Pansy Patrol at the Atlanta Pride parade? I tried, in my way, to shield you with my love. I tried to love you out of the reach of the clutches of those who do not want you to exist.

I did what a once-poor, erstwhile-single black mama could do outchea.

I tried to make the lemonade I wanted to see in the world. Were you watching how I did it?

I was not correct earlier when I said I was the main ingredient in the lemonade recipe. I'm the main ingredient in my recipe. You have your own lemonade to make now.

Love,

Mama

P.S. Call me anytime.

P.P.S. I should have said re-ci-pes. I know you find most poetry annoyingly cryptic, but I've already subjected you to this, for my good reasons. Here, however, is a recipe of mine that should be plain enough for your tastes, I think:

Recycling on Doomsday (or Another Inconvenient Truth)

by Shawna Floyd Artist

It makes no sense

to you.

You tell me

in passing

at the recycling center.

We don't

know each other

but you need to vent.

Thoughtless

recyclers

dropping their bottles

cans

cardboard

magazines

in the designated places

while

leaving their cars

with the engines on.

I nod

because I understand

where you are

coming from.

I do not tell you

that you

are my climate change.

I do not welcome you—

veteran though I am—

to the brink of destruction.

So it follows

that I cannot then

correct

what I've not said

by saying, "Brinks, really.

Welcome to the brinks

of destruction

because it is always

something."

I do not

tell you

to go ask

Lucille Clifton

if you don't believe me

about the daily

attempts on my life.

Because I'm not

in a celebrating mood.

I will drop

my kombucha bottles

in the proper receptacle

for clear glass

but I will not

save this world

for you

to lynch and burn me

in my military uniform...

brown glass goes over here...

for you to graduate

summa cum laude from

"White" Only

water fountains

and "Colored" Only

water fountains

to Flint, Michigan's

poisoning

to "First" World

water

and "Third" World

drought.

I will not

save this world

for you

to graduate

Phi Beta Kappa

from Uniontown, Alabama

with your

Dakota Access Pipelies.

If all you have

is a hammer

everyone looks like

a nigger.

If all you have

is a gun

everyone looks like

an indian.

Green glass

clinks

to pieces

like Reconstruction

or the Voting Rights Act.

With the plastic

I am freewheeling

casual

and unconcerned

like that smiling

shopping

white woman

in that

mall die-in photograph.

I throw the containers

without a care.

I didn't tell you

that you

are my nuclear war.

Steel cans over here.

I taught my children

to tell time

on our people's clock.

We have lived

through a million

eleven fifty-nines

and have faced down

a million midnights.

These aluminum cans

are for us.

This is not

a movie.

There are no

wise indians or

magical negroes

coming to your rescue.

Because it is

your rescue

you are concerned with.

Because we

we have been

nearly destroyed

over and over

and over

and over

and over

and over again.

But you

are a climate change denier.

I will not save

this world.

I will not recycle

or reuse it

to find

the old threat

with new kicks—

white hands

jabbing coffee shops

like flags

into the land.

Manifest Destiny

in our macchiatos.

I will not

help you

save this land

water

air

to live myself

redrawn

gerrymandered

to find

tyranny

in my democracy

slavery

in my

13th amendment

to find

myself

around smiling

white faces

who say

they didn't

plant the flag

but whose hands

will never

give up

their coffee cups.

You can't put right

spoiled milk.

You throw it away.

But I didn't tell you this

at the recycling center.

You were

as you have always been

preoccupied

with your recycling

tick tick ticking along

ticking away

like a doomsday clock.

*All definitions from Oxford University Press, 2019, Lexico.com.

//

Shawna Floyd aka Shawna Floyd Artist makes art to hear herself think, feel and be over the racket of—tell it, bell!—"the imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy," over the din of trauma, over the liveliness of her family; to do some of her clearest thinking and knowing; to enshrine messages to herself and to her children; to gnaw back on what is gnawing at her; to get and stay free. She is a poet, writer, singer-songwriter, lover, gardener/landscaper in the capitol A of the Dirty South who recently sent her son to a one semester art boarding school on the occasion of his senior year in high school. She is known in some circles and hearts as Shawna J. Floyd. J is for justice.